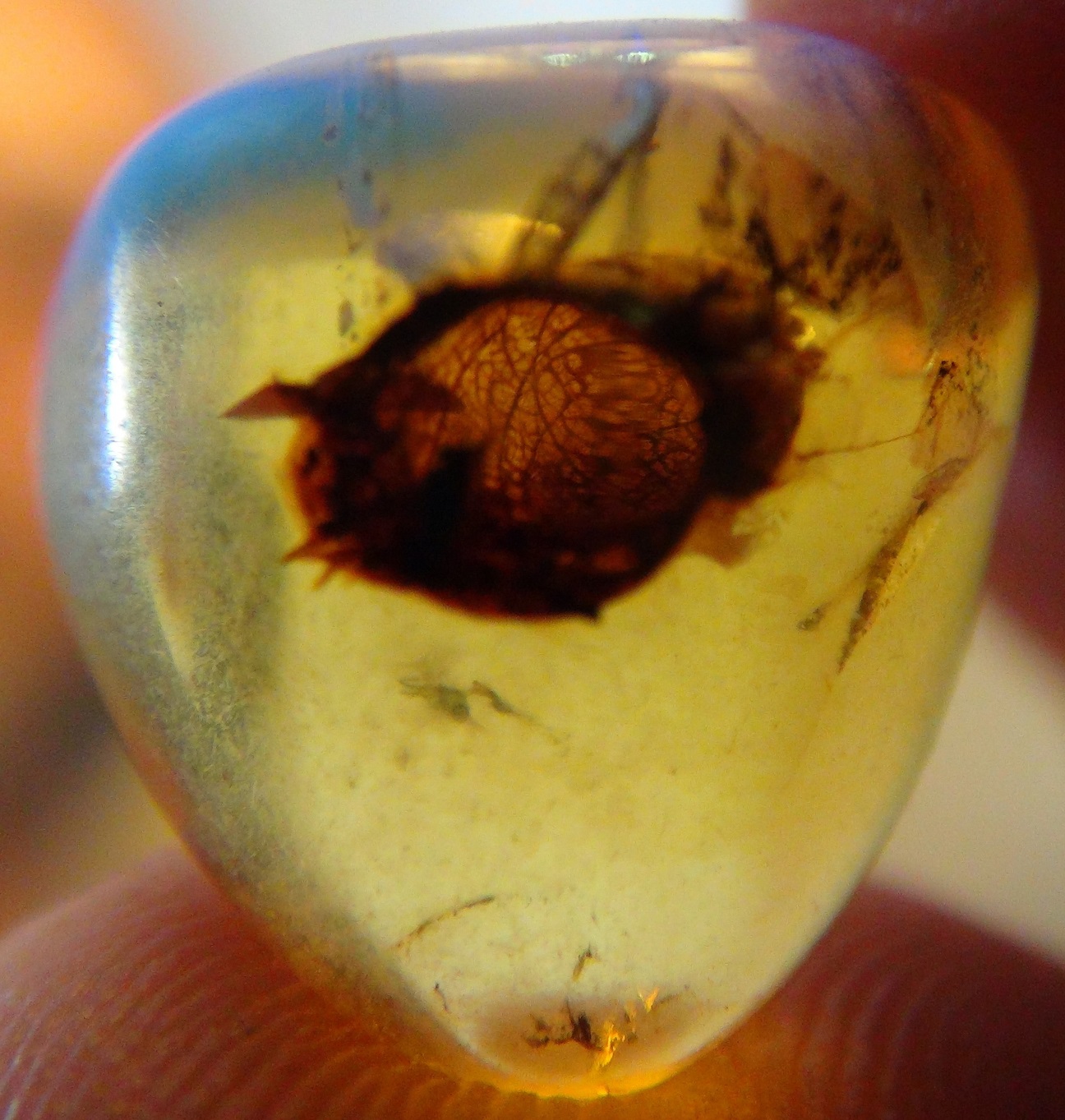

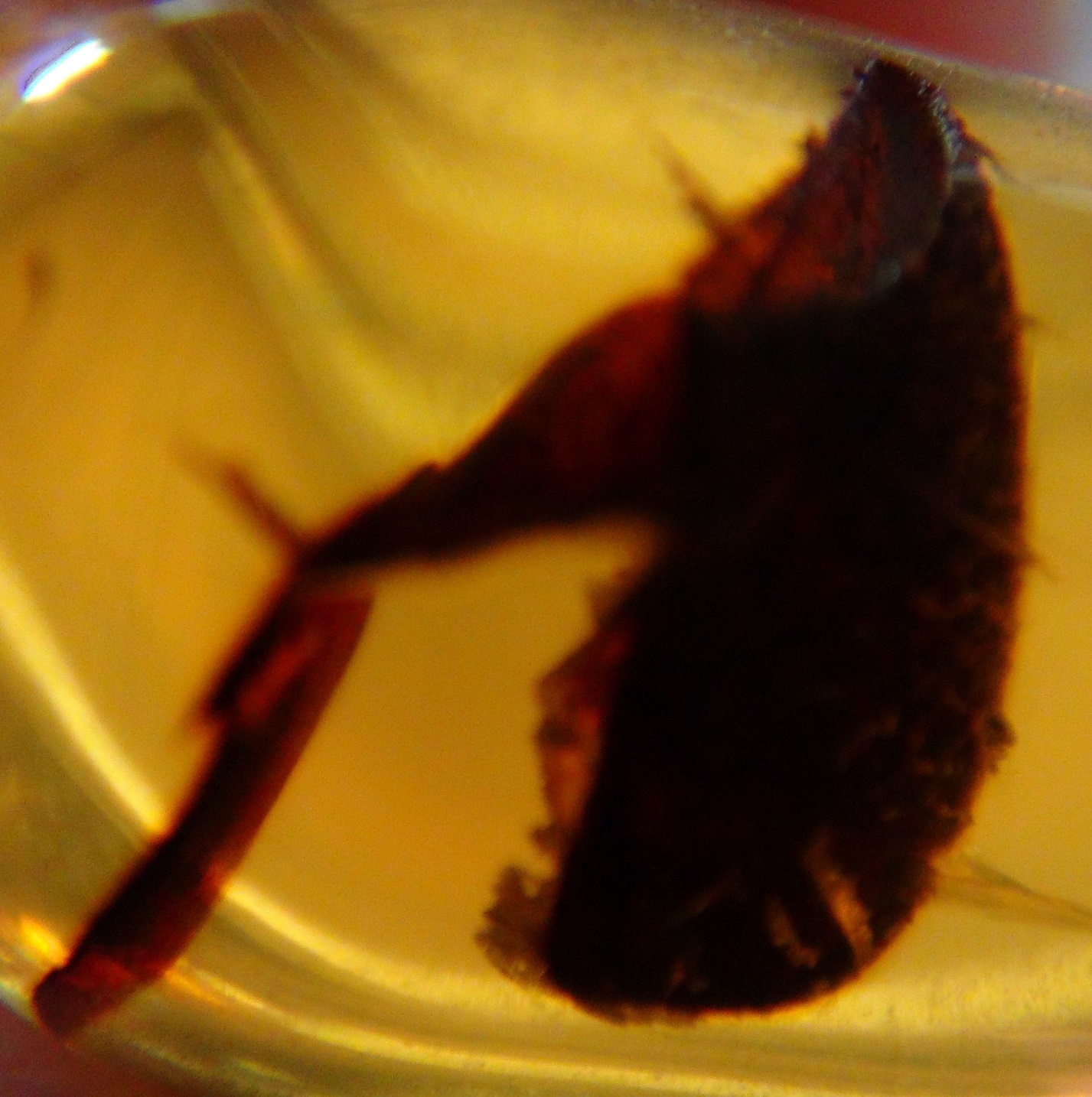

Nepenthes (/nᵻˈpɛnθiːz/), also known as tropical pitcher plants, is a genus of carnivorous plants in the monotypic family Nepenthaceae. In the photo below we can see an insect was perhaps about to enter the pitcher and die when either the plant fell from the tree into the amber or a blob of amber fell on the flower, scientists who study amber flows are actually able to calculate fairly accurately the most likely scenario.

Some scientific papers on flowers in amber (Although pitcher plants have been described in younger ambers such as Baltic amber from the Eocene epoch have been described no attempt has been made yet to document all the pitcher plants that occur in Burmite amber.)

Some scientific papers on flowers in amber (Although pitcher plants have been described in younger ambers such as Baltic amber from the Eocene epoch have been described no attempt has been made yet to document all the pitcher plants that occur in Burmite amber.)

Poinar, G.O.Jr., Buckley, R. & Chen, H. 2016. A primitive mid-Cretaceous angiosperm flower, Antiquifloris latifibris gen. & sp. nov., in Myanmar amber. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 10(1), 155-162.

Poinar, G.O.Jr. & Chambers, K.L. 2005. Palaeoanthella huangii gen. and sp. nov., an Early Cretaceous flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. Sida, 21(4), 2087-2092.

Poinar, G.O.Jr., Chambers, K.L. & Buckley, R. 2007. Eoëpigynia burmensis gen. and sp. nov., an Early Cretaceous eudicot flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 1(1), 91-96.

Poinar, G.O.Jr., Chambers, K.L. & Buckley, R. 2008. An early Cretaceous angiosperm fossil of possible significance in rosid floral diversification. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 2(2), 1183-1192.

Poinar, G.O.Jr., Chambers, K.L. & Wunderlich, J. 2013. Micropetasos, a new genus of angiosperms from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 7 (2), 745-750.

Our taxa list is based on the amazing work of Dr Andrew J. Ross who has prepared a newer updated list and kindly offers it for free download

Amber lovers and Paleos can dig up the latest updated version here:

https://www.nms.ac.uk/media/1154465/burmese-amber-taxa-v2017_2.pdf

"Nepenthe" literally means "without grief" (ne = not, penthos = grief) and, in Greek mythology, is a drug that quells all sorrows with forgetfulness. Linnaeus explained:

"If this is not Helen's Nepenthes, it certainly will be for all botanists. What botanist would not be filled with admiration if, after a long journey, he should find this wonderful plant. In his astonishment past ills would be forgotten when beholding this admirable work of the Creator!"

[translated from Latin by Harry Veitch (1897). "Nepenthes". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society.]

The plant Linnaeus described was N. distillatoria, called bāndurā (බාඳුරා), a species from Sri Lanka.

The name "monkey cups" was discussed in the May 1964 issue of National Geographic, in which Paul A. Zahl wrote:

The carriers called them "monkey cups," a name I had heard elsewhere in reference to Nepenthes, but the implication that monkeys drink the pitcher fluid seemed farfetched. I later proved it true. In Sarawak I found an orangutan that had been raised as a pet and later freed. As I approached it gingerly in the forest, I offered it a half-full pitcher. To my surprise, the ape accepted it and, with the finesse of a lady at tea, executed a delicate bottoms-up.

Symbioses

A lower pitcher of N. attenboroughii supporting a large population of mosquito larvae. The upright lid of this species exposes its pitchers to the elements such that they are often completely filled with fluid

Nepenthes bicalcarata provides space in the hollow tendrils of its upper pitchers for the carpenter ant Camponotus schmitzi to build nests. The ants take larger prey from the pitchers, which may benefit N. bicalcarata by reducing the amount of putrefaction of collected organic matter that could harm the natural community of infaunal species that aid the plant's digestion.

Nepenthes lowii has also formed a dependent relationship, but with vertebrates instead of insects. The pitchers of N. lowii provide a sugary exudate reward on the reflexed pitcher lid (operculum) and a perch for tree shrew species, which have been found eating the exudate and defecating into the pitcher. A 2009 study, which coined the term "tree shrew lavatories", determined between 57 and 100% of the plant's foliar nitrogen uptake comes from the faeces of tree shrews. Another study showed the shape and size of the pitcher orifice of N. lowii exactly match the dimensions of a typical tree shrew (Tupaia montana). A similar adaptation was found in N. macrophylla, N. rajah, N. ampullaria, and is also likely to be present in N. ephippiata.

Nepenthes pitcher plants are typically carnivorous, producing pitchers with varying combinations of epicuticular wax crystals, viscoelastic fluids and slippery peristomes to trap arthropod prey, especially ants. However, ant densities are low in tropical montane habitats, thereby limiting the potential benefits of the carnivorous syndrome. Nepenthes lowii, a montane species from Borneo, produces two types of pitchers that differ greatly in form and function. Pitchers produced by immature plants conform to the ‘typical’ Nepenthes pattern, catching arthropod prey. However, pitchers produced by mature N. lowii plants lack the features associated with carnivory and are instead visited by tree shrews, which defaecate into them after feeding on exudates that accumulate on the pitcher lid. We tested the hypothesis that tree shrew faeces represent a significant nitrogen (N) source for N. lowii, finding that it accounts for between 57 and 100 per cent of foliar N in mature N. lowii plants. Thus, N. lowii employs a diversified N sequestration strategy, gaining access to a N source that is not available to sympatric congeners. The interaction between N. lowii and tree shrews appears to be a mutualism based on the exchange of food sources that are scarce in their montane habitat.

The AAKZ archive contains not only pitcher plants in amber but also tree shrews in amber. Please feel free to contact us for further data should you require.